The following year the expedition’s work-force was increased in number, employing from eight to twelve men, twenty-four to thirty-six boys, guards, a water-carrier and of course a reis.

They were learning fast; it’s hard to believe that Maggie, at least, did not study archaeology during the summer, if only learning from her brother Fred. They certainly read fairly widely about Egypt and Egyptian history, including books by Amelia Edwards, Petrie, Naville, and a Professor Wiedemann. They also realised that they needed more help on site.

Anyway, having more-or-less excavated the first court of the temple the year before, the expedition then turned its attention to the pylon beyond it. This presented them with their first real archaeological challenge.

Of course we need to remember the circumstances that they were working under; they were not excavating a structure, as such, but mounds of sand and gravel, below which fragments of foundation survived. What was more, the site had been rebuilt several times.

"Piankhy blocks" are now known to be in fact carvings showing the arrival at Karnak of Nitocris, later the God’s Wife of Amun, Nitocris I (reigned ca. 655-584 BCE), accompanied by a powerful military force transported on ships, in ca. 654-656 BCE (sources vary as to the precise date).

"Piankhy blocks" are now known to be in fact carvings showing the arrival at Karnak of Nitocris, later the God’s Wife of Amun, Nitocris I (reigned ca. 655-584 BCE), accompanied by a powerful military force transported on ships, in ca. 654-656 BCE (sources vary as to the precise date).

Nitocris was the daughter of Psammetichus (Psammetik) I, the Persian vassal ruler of Egypt, who by sending both force and, it seems, considerable amounts of valuable items, forced the reigning God’s Wife, the Kushite Shepenupet II, to adopt her as her successor. This is seen as marking the end of Kushite (i.e. Nubian) influence in Egypt, following the XXVth "Kushite" Dynasty. Until that point Thebes had still regarded itself as a Kushite vassal city.

The expedition had problems with salts damaging pottery and statuary – salt has since become a huge and extremely serious problem at not only Karnak but other sites – which they managed to control by soaking items in water.

In fact in one interesting passage they reveal that De Morgan once had had a scheme for flooding the entire Karnak site, using the water that he thought flowed from the Nile into the sacred lakes. However - unsurprisingly - "the practical difficulties were so great… that it was never carried out."

Still in search of foundation-deposits, they dug at the eastern corner of the wall, a likely spot for them. Although they did not find foundation-deposits, they did find a great number of statues, which they believed were deliberately buried there. (Indeed, sometimes temples did have a "clear-out" of statues, which they buried in the temple grounds").

In the search for foundation-deposits they made excavations at points around all the walls of the Temple; they were also to do this during the following year. And it was whilst doing so they found a tiny underground room, which they described inaccurately as a "crypt", at the lake end of the Temple.

It seems very significant of their state of mind that, on finding a hole leading from this, they jumped to the conclusion that it was a "treasure-chamber". At the back of how many minds over the years has been that gleam of gold everywhere which Howard Carter described when first looking in to King Tut’s tomb, more than 20 years later!

Excited, they took elaborate precautions overnight, spreading sand, in which they wrote their initials, around the entrance, and placing an armed guard in front. And then came disappointment; the "treasure-chamber" only contained a few fragments of ancient rubbish!

Maggie and Nettie – like other Egyptologists of the time - had to learn fast on the job, not least how to cope with overbearing officials, who were possibly motivated by the Anglo-French rivalry noted above.

At this time the rest of the Precinct of Amun at Karnak was being excavated by the French-run Antiquities Service, work being directed by a M. Legrain. In early February 1896, Legrain descended on the Temple of Mut, and demanded that all the various pieces of statuary that had been discovered there, which were being kept by the expedition at the Luxor Hotel, should be taken to the Antiquities Service magazine at Karnak. Not only would this deprive Maggie and Nettie of the pleasure at being able to look at what they had found, but would have also prevented the pieces from being photographed, drawn, and described by presumably not only Maggie and Nettie, but other Egyptologists, too.

Maggie described in a letter to her mother what happened. "I very nearly wept, and called Fred [her brother], who was slightly rude. M. Legrain became much more polite and finally said that if we chose to take the whole responsibility of their safety, we could take them back…"

They chose the last week of February to close the dig on, and were intending to travel to Cairo, and then home, during the first week of March. They therefore ceased to employ a number of the boys. One of these, however, still hanging around the site, was to make a significant discovery at the rear, southern, end of the temple on the bank sloping down to the lake. Investigating a half-buried block of stone that had been thought of no importance, he felt a carved foot underneath.

The expedition worked hard to excavate this statue before sunset, as it was Ramadan. They managed it, and found that it was a rare (for the site) complete statue, with another statue buried beneath it. They left two armed guards to protect it overnight (a by no means unreasonable precaution, in fact), and the next morning found Percy Newberry already examining the statue. He was able to reveal to them that it was of Senmut, an official to Queen Hatshepsut; later he was to be revealed as the architect of the Temple.

Legrain by this time seems to have been more co-operative, as he helped the expedition, together with a Mr. Dixon of the Land Taxing Commission at Luxor, to move the statues up the bank.

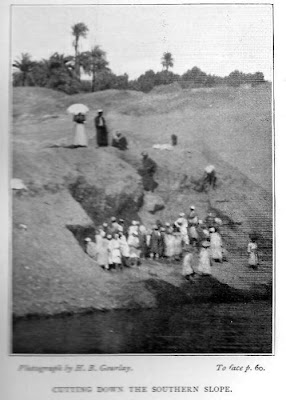

As a slightly hurried end to their season, Maggie and Nettie decided to "cut down" the southern bank of the lake, in the hope of finding more, and a remarkable photo was taken of them doing this.

Although their contract with the Antiquities Service had specified that their finds were sent to the Cairo Museum, it was however customary for expeditions to be allowed to keep certain duplicate items for themselves (in fact this was still allowed up to the mid 1980s). Unfortunately, Egypt has occasionally lost some valuable antiquities in this way, sometimes through dishonest behaviour on the part of the excavator, as was the case with the famous head of Nefertiti, or simply through a misunderstanding of what the item actually was.

And so, the Antiquities Service let Maggie and Nettie keep the head of a God, thought to be Min, a statue of Ramesses II, and the head of a statue of Ramesses III.

However, the head of "Min" was, much later, found to in fact be the head of Amun, and was one of only two that have ever been discovered. It was sold in 1991 at Christies for no less than £572,000 (the equivalent of approximately $1 million at the time)!

This was by no means all. The expedition was also given a 26th Dynasty statue of Ser, a son of a pharaoh, which was sold in 1977 for $190,000.

Ironically, then, their treasure turned out to be not in their imagined "treasure-chamber" (most likely in fact a store for sacred vessels), but the "duplicate" statuary that they were given.

So far, so very good, then. However, in October 1896 Archbishop Benson died suddenly – appropriately, perhaps, during a church-service - whilst visiting the Gladstones at their home, Hawarden.

Maggie had always been close to her father, and it is possible that in some way his death may have contributed, if only indirectly, to her later mental illness. However, for the moment, continuing the excavations in 1897 was the perfect reason for a Benson family holiday in the country, and so Maggie, her mother Mary, and her brothers Fred and Hugh (who was later to convert to Roman Catholicism) set off for Luxor together.

It was an important find; in fact the head is one of the great works of Egyptian portraiture. This alone would have made the entire season a success, and so we can imagine that everything must have looked extremely promising indeed to Maggie and Nettie. Indeed, it can only make us wonder just what might have been were they able to continue; indeed, how it all might have come to affect the history of Egyptology itself.

It was an important find; in fact the head is one of the great works of Egyptian portraiture. This alone would have made the entire season a success, and so we can imagine that everything must have looked extremely promising indeed to Maggie and Nettie. Indeed, it can only make us wonder just what might have been were they able to continue; indeed, how it all might have come to affect the history of Egyptology itself.

The expedition now, unsurprisingly, concentrated its effort around the rear, southern wall of the Temple, an area that contained a Ptolemaic era shrine. And yet again they found large numbers of statues. On the first day alone, they record, they found fourteen pieces of statue, including a Saite period head, which they believed to be female, but which is now known to be in fact of a man.

Their aim was also conservation, and as they had during the previous season tried to replace stonework in what they believed to be its original position, and to repair statues.

It was, archaeologically, an outstanding season, and they certainly intended to return the next year. Nettie wrote to Percy Newberry saying that they were planning to build an excavation-house on the site, for storage and accommodation. They also tentatively planned to dredge the Lake for objects (this in fact was not done until this year, 2008).

But unfortunately it was all never to be, as Maggie’s health was soon to seriously break down, to the extent that her life was threatened.

The family had to remain in Luxor until June, with the Luxor Hotel being kept open especially for them "at much expense after all [other] visitors had departed."

In fact even after the publication of The Temple of Mut in Asher, Maggie’s career in Egyptology was not quite over.

In 1900-1901, Maggie and Nettie, together with "Aunt Nora" – a Mrs. Sidgwick, who was the elder sister of British politician Arthur Balfour - were to visit Egypt again, and stayed with Newberry in his rented house on the West Bank at Luxor.

(Coincidentally they were to make a torch-light visit to the Valley of the Kings on the same evening that the news of the death of Queen Victoria. Like so many other Victorians, Maggie realised that it was the passing of an age).

It has long been thought that they were travelling merely as tourists. However, the Egyptologist Herbert Winlock, writing much later about a bowl found by Newberry at this time, mentioned that Newberry had said in a letter to Theodore Davis (see below) that: "My friends Miss Benson and Miss Gourlay are going to join me at Thebes where we intend to work together."

Plainly the trip must have been arranged with Newberry, as they stayed at his house. But had, in fact, Maggie and Nettie actually decided to work with him?

Maggie put it this way: "Our plans both for Egyptology and travelling must seem rather like the ‘glittering chameleon.’ Here is a new departure, the most definite thing, in a sense, that has yet turned up. Mr. Newberry has been planning to write a history of Egypt - a big history and a standard one – to be more complete, but especially more literary than Petrie’s. It appears that he approves of my literary (!) powers, and he has asked me [and presumably also Nettie?] to help him. He is going to try to get his American millionaire to finance the work…"

The "American millionaire" was Theodore Davis, who was to finance a number of archaeologists working in the Theban area. He is best known for his attempts to fully excavate the Valley of the Kings. In 1900, the year of Maggie and Nettie’s visit, Davis had given Newberry £250, to excavate Theban Tomb 100, made for an Eyptian called Rekhmire, as well as ten other tombs in the area of Abd el-Qurna village.

Newberry expected that the book would take two years to write, and it would involve Maggie visiting museums in Britain and in Europe. She was also busy at the time with editing a book of sermons by her father. What was more, she (at least by now) seems to have been in two minds about Egyptology, writing that "I can’t feel that Egyptology is the thing most worth doing in the world, though I feel that about most other things while I’m doing them… things… like Egyptology, opened just when I could do nothing else."

However, Percy Newberry made it clear that what he valued above all was Maggie’s literary style. After all, she had written several, quite popular books. And in fact her writing-style is very good; she could avoid the stiff, wordy Victorian style, when necessary; her communication-skills were undoubtedly excellent. (And it does raise the question whether Newberry hoped for her help in getting funds from Davis).

Newberry did not press her for an answer, allowing her time to think it over, but she obviously declined, in the end. Still, she seems to have at least seriously considered the proposal, even seemingly changing her travel-plans when journeying back to England in order to travel up through Italy to "See the museums there".

It is a great pity that, in the end, she did not write the book. Despite her beliefs that Nettie was the Egyptologist, rather than her, she had exactly the sort of questioning, analytical mind and methodical approach, able to learn from mistakes and experience, that is needed. And furthermore, there is no doubt that she had great intelligence; it was often said at the time that if she had been allowed to read for a degree at Oxford she would have obtained one.

Consider, for example, her approach to Egyptian religion, a subject which it is plain from The Temple of Mut in Asher fascinated her. She was to write when seeing the ritual texts on the walls of tombs in the Valley of the Kings that "I wish one could work out this religion question". She criticises the standard guide-book of the day, Baedecker, for its inadequate descriptions of the scenes, writing that it "sounds like Lear’s Nonsense Book!"

Given that she was the daughter of a Victorian Archbishop of Canterbury, she might well have taken the opinion that Egyptian religion was all simply "nonsense." But on the contrary, she understood that all religions have far more in common than their practitioners would often like to admit. Brought up amongst cathedrals, she seems to have had an inner understanding of what made the essential nature of all religion.

‘A hope deferred, but sure’

More and more, the Egyptological work of Maggie and Nettie is being appreciated, in an age when women’s achievement can be recognised. They appear on lists of famous Egyptologists; they have Wikipedia entries, and other internet sites about them.

And yet, how much more there could have been! Had Maggie not fallen so ill… had the expedition continued (as it fully intended to do)… had the Benson and Gourlay team (for it would surely have been something of a joint effort) gone on to write Percy Newberry’s book… had, simply, the abilities of women been more fully recognised at the time!

However their work has been carried on at the "Temple of Mut in Asher". Brooklyn Museum and Johns Hopkins University carry on the work there, under the supervision of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, and perhaps, if you seek the epitaph of Maggie and Nettie as Egyptologists, it with the carrying on of the work they started.

No comments:

Post a Comment